From the first time I travelled overseas, almost 25 years ago now, I believed that my Australian passport meant something. I was ten and bursting with grown-up pride to have the blue document with the crest in my bag. I’ve spent most of my adult life out of the country, studying, travelling, working, living. And up to 18 months ago it never occurred to me that in doing so I was somehow invalidating my birth right. On the contrary, DFAT was always there to tell you what to do if you needed help. When I travelled through Africa a decade ago, I knew where our embassies were, and where they weren’t, I was told the Canadians, or the British, would be there if I needed it. To be an Australian was to be privileged and safe. It was nice to have that warm sense of security.

At uni I learned that Australia was the only western democracy without a human rights declaration. Not to worry, in theory there are implied rights for citizens in the constitution. Plus, international law stipulates that nationals have a right to return. Given Australia’s record with international law in general, that shouldn’t have been any reassurance.

On a forum several weeks ago, I was called entitled for wanting to come home and see my family. You’re damn straight I’m entitled. That’s literally what that passport is supposed to give you, entitlements. Otherwise, what is the bloody point? Citizenship is not only a privilege, it is a legal status, and it comes with rights, the most basic of which is a right to return.

Can you imagine if the rest of the world behaved as Australia has? If countries with populations in the tens or hundreds of millions suddenly decided to refuse their citizens abroad re-entry unless they could pay copious amounts of money to get in? If they were left to indefinitely depend on the charity of strangers in foreign lands for food and a roof over their head? If everyone behaved as selfishly and illegally as the Australian government, there would be chaos.

For me, the saddest part of this is I suspect that if other governments tried, their citizens would be in uproar for their fellow compatriots. Decades of rhetoric around ‘locking out’ threats has made the Australian public insular and cruel. I have always been an advocate for more humane immigration policies, always been ashamed by how Australia treated refugees, but even I never thought we’d abandon our own. How a government treats it’s least advantaged should concern everyone, because it is indicative of what they will do to you if they think they can get away with it.

Other ‘ideas’ I’ve come across are that certain Australians may be more deserving to come home than others. The keyboard warriors love to question whether someone is a ‘real’ citizen. I can’t say for certain what they mean, but I strongly suspect it has to do with the colour of people’s skin or how their voice sounds. It may make people (racists) feel better to tell themselves that they are ‘more Australian’ than others, but that doesn’t make it true. The hatred and vitriol that has been spat towards dual citizens or people of mixed heritage is appalling. Let me say it again, a citizen is a citizen. They have the exact same legal rights and status whether they were born in India, descended from the convicts, are Indigenous Australians, or third generation immigrants. Whether they hold a second or third passport or have never left the country. You can repeat as many times as you want this idea that there are ‘true aussies’, but it doesn’t make it fact. The only people who could arguably claim an increased right to anything are indigenous persons, and funnily enough I haven’t seen any of them advocating for abandoning fellow nationals.

By some stroke of amazing timing I became a naturalised French citizen in 2019, and it is somewhat of a relief to now carry a passport for a country that I know will protect me. But I am first and foremost and always will be, an Australian. It is the land of my birth, where I grew up, where my family is. It defines who I am as much as being a woman, partner, daughter, sister, friend. You don’t get to tell me that because I fell into an expat life years ago, because I now have ties to another country, I am no longer what I have always been.

Australians overseas keep hearing ‘you should have come home’, ‘you shouldn’t have left’, ‘you should have stayed’. First of all, we were never explicitly told to come home or risk being locked out. But you know what? The bigger issue is that someone should have told me my passport meant shit all. Australians should have been informed that unlike other nations, their government would not respect citizens rights.

When this is all over, when international travel resumes to something resembling normal, every Australian leaving the country should do it with the knowledge that if shit hits the fan, you are on your own. Never again can we allow Australians to leave for abroad with the false sense of security that if there is trouble, you will always have a place to call home.

Since I began my blog in

Since I began my blog in

Throughout his story he repeatedly shrugs his shoulders and says ‘what can I do?’ and I nod dumbly and understandingly. But he repeats it when we say goodbye, and I realise it’s not a rhetorical question. ‘What would you do?’ he asks, pleading for some kind of guidance or advice. I don’t know what to tell him. I can’t tell him his situation is hopeless or that he’s done anything wrong. And I can’t judge any one decision he’s made. ‘I would have left as well…’ I say, ‘but I wouldn’t stay here’. He nods sadly, ‘I just didn’t want to fight for the Taliban’ he says again before he walks away.

Throughout his story he repeatedly shrugs his shoulders and says ‘what can I do?’ and I nod dumbly and understandingly. But he repeats it when we say goodbye, and I realise it’s not a rhetorical question. ‘What would you do?’ he asks, pleading for some kind of guidance or advice. I don’t know what to tell him. I can’t tell him his situation is hopeless or that he’s done anything wrong. And I can’t judge any one decision he’s made. ‘I would have left as well…’ I say, ‘but I wouldn’t stay here’. He nods sadly, ‘I just didn’t want to fight for the Taliban’ he says again before he walks away. He asks where I’m from, expresses amazement that I have come so far, and I do the usual living in Paris spiel. Recognition flashes over his face and he asks if I was ok when the attacks happened last month. I don’t know why after all the people I’ve met his concern still takes me aback, but it does. I assure him everyone I know was ok. He nods his head, ‘that is good…. but what happens in Paris, it happens every day in Afghanistan.’ He nods goodbye and walks away, but not before delivering the most common line I’ve heard from refugees from Eritrea to Kuwait, ‘we just want a life’.

He asks where I’m from, expresses amazement that I have come so far, and I do the usual living in Paris spiel. Recognition flashes over his face and he asks if I was ok when the attacks happened last month. I don’t know why after all the people I’ve met his concern still takes me aback, but it does. I assure him everyone I know was ok. He nods his head, ‘that is good…. but what happens in Paris, it happens every day in Afghanistan.’ He nods goodbye and walks away, but not before delivering the most common line I’ve heard from refugees from Eritrea to Kuwait, ‘we just want a life’.

I generally don’t tend to head north at this time of year, at most times of year for that matter, and thankfully for my vitamin d levels in less than two weeks I’ll be on a beach in Sydney and temperatures in single digits will seem like a distant memory. But right now I’m on a train heading to northern France, where the forecast is predicted to be rain, cold and wind, three things that I hate. And I’m heading to a place that is so unappealing its been nicknamed ‘La Jungle’.

I generally don’t tend to head north at this time of year, at most times of year for that matter, and thankfully for my vitamin d levels in less than two weeks I’ll be on a beach in Sydney and temperatures in single digits will seem like a distant memory. But right now I’m on a train heading to northern France, where the forecast is predicted to be rain, cold and wind, three things that I hate. And I’m heading to a place that is so unappealing its been nicknamed ‘La Jungle’. The Jungle actually refers to several squatter camps that have sprung up around the northern French town of Calais, where the Eurostar tunnel takes travellers across the channel to England. While refugees have gathered here for years trying to jump trucks, trains, cars or ferries to get to the UK, in the past year numbers have substantially increased and there are now thousands of people. Some have

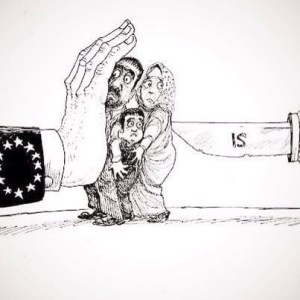

The Jungle actually refers to several squatter camps that have sprung up around the northern French town of Calais, where the Eurostar tunnel takes travellers across the channel to England. While refugees have gathered here for years trying to jump trucks, trains, cars or ferries to get to the UK, in the past year numbers have substantially increased and there are now thousands of people. Some have  Such an approach has failed. Coinciding with my weekend is the second round of the French regional elections, where Marine Le Pen, France’s terrifying duplicate of Pauline Hanson or Donald Trump, is poised to win the first region ever for her far right-wing party the Front National. What is amazing to me is how many people in the previously socialist north seem to be voting for Le Pen as a

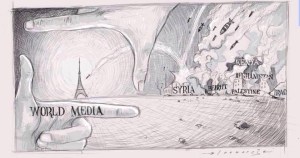

Such an approach has failed. Coinciding with my weekend is the second round of the French regional elections, where Marine Le Pen, France’s terrifying duplicate of Pauline Hanson or Donald Trump, is poised to win the first region ever for her far right-wing party the Front National. What is amazing to me is how many people in the previously socialist north seem to be voting for Le Pen as a  I’ve spent a lot of time since starting this project obsessing over how governments and people can be so dismissive of refugee’s human rights.

I’ve spent a lot of time since starting this project obsessing over how governments and people can be so dismissive of refugee’s human rights.

Many people asked me why I didn’t take more photos, or even video footage. It’s important to remember that these people are refugees, which by definition means that they are fleeing persecution, and most likely do not want their identity to be revealed to authorities back home before they have found safety and a durable solution. In Syria there have even been stories of Assad’s government identifying individuals on social media and raiding their property, or worse, punishing loved ones they have left behind. To add to this, many journalists operating in the field have

Many people asked me why I didn’t take more photos, or even video footage. It’s important to remember that these people are refugees, which by definition means that they are fleeing persecution, and most likely do not want their identity to be revealed to authorities back home before they have found safety and a durable solution. In Syria there have even been stories of Assad’s government identifying individuals on social media and raiding their property, or worse, punishing loved ones they have left behind. To add to this, many journalists operating in the field have